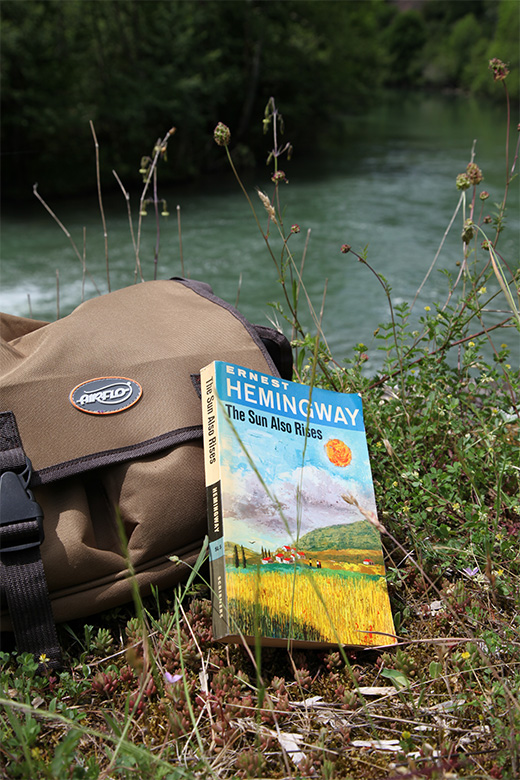

Like many fly fishermen, I first learned of northern Spain’s Irati river in Ernest Hemingway’s novel The Sun Also Rises. Beginning in the green forests of Franco-Spanish Basque Country – where additional rocky headwaters widen its path – the river’s south-western route flows towards the region of Aragon via Navarra, in which the American writer spent a great many summers ‘fishing, drinking, writing and bullfighting’, as is fabled, in his favourite part of Spain.

Of those four merry pastimes it is predominately the drinking and the bullfighting that concern this particular novel; the fishing is but a fleeting moment wedged in-between. But oh what fishing, as those who have similarly stumbled upon Hemingway’s lucid, semi-autobiographical narrative will testify; wild brown trout pulled from white rushing water, amidst a valley of woods, wheat fields and wineries.

Aribe and the Irati River

Research

Last spring, land-locked in London and with these visions in mind, I began looking into the Irati river, to see whether or not Hemingway’s Spanish fly-fishing idyl remained accessible today. My father and I had discussed embarking on a fishing holiday of some kind in the summer, and I was hopeful this could be it. Dad spent his youth on South African trout streams, wading fast waters in the shadow of the Drakensberg mountains. Since then he has made the best of the comparatively sedate Tywi Valley in West Wales, and its declining trout and salmon. He, too, fancied a change of scenery.

Initial research involved trawling websites and fishing blogs, first to pin-point Hemingway’s actual spot (fictionalised for the novel, though very much a real location), and second to decipher Spain’s angling regulations and permissions. Thereafter I faced two options: spend a small fortune on an all-inclusive guided ‘Pyrenean’ fly-fishing package, or piece together a DIY itinerary. After much back and forth with various tour operators (whose miserly-minded discourse proved unhelpful to say the least), I inclined towards the latter, purchasing Philip Pembroke’s Fly Fishing in North East Spain, a compact and reasonably-priced guidebook.

Hemingway novels inspire generations into outdoor explorations

With simple maps, photographs and experience-informed text, Pembroke addresses the Irati’s catch-and-release boundaries, and the water’s depth, quality, fish species and points of access. He even includes a black-and-white of old Ernest, smiling riverside with two beautiful brownies dangling at his sides (proof that I am far from the only fisherman to have pursued the ‘Hemingway experience’). Nevertheless, I was still having trouble comprehending exactly how to procure our permits.

Regulations and restrictions

Fishing in Spain is governed on a regional basis, and Navarra – a notoriously over-fished province – is fiercely regulated. Being a comparatively wealthy area of the country renowned for its outdoor pursuits, there are a great many licensed fishermen competing for its waters; only eight day permits are issued for Hemingway’s stretch of the Irati. As I was just about giving up with Navarra’s environment agency website, I received a reply-email from a wonderful Frenchman named Yvon Zill. A Basque Country guide based on the French side of the Pyrenees, Yvon kindly agreed to drive over the border to meet us for a single day’s fishing on the Irati. He would swiftly reserve our permits for the full three days, “as now there is very limited availability”, which Dad and I would then fish alone. Flights and accommodation booked for the middle of June, we were off to the Pyrenees.

It is a brief single chapter, right in the middle of The Sun Also Rises, that so well encapsulates fishing the Irati. No doubt readers little interested in McGinty flies, leaders and landing nets tend to skim-read this somewhat tangental section, while those otherwise inclined pore over every sentence. The novel’s 20-something protagonist Jake Barnes has stopped-off in northern Navarra, with his buddy Bill, en route to Pamplona for the famous ‘running of the bulls’. They’ve come up from the boozing bustle of Paris for a week’s quiet fishing in the Basque hills, staying in Burguete, a small village high up beside the French border, in a cold, creaky hotel.

True-to-life descriptions

Hemingway’s firm familiarity with the area informs a true-to-life description in the book of the pair’s hike through the green and lush countryside, to the edge of a dam just downriver from the little red-roofed Spanish farming town of Aribe. Here I booked a two-bedroomed apartment for Dad and myself, at the big and rustic Hotel Aribe overlooking the river that in Hemingway’s day must have still been a working ‘baserri’ farmhouse. To get there we flew to Bilbao, hired a car and drove three hours east via Pamplona for supplies. The road up from Pamplona was a pretty one, growing progressively wooded and beech-green as we ascended Navarra’s chalky hills. We made town just before sunset, and stood on Aribe’s perimeter bridge watching fisherman working the evening rise. You couldn’t imagine a more enticing scene.

Yvon Gill, our fantastic guide

Our guide

Yvon greeted us bright and early outside the hotel the next morning. Enthusiastic and jolly, he introduced the river and its geography, but also the surrounding landscape and wildlife, pointing out a pair of nesting red kites, while we fixed our waders and rods. He knows Aribe well, having guided here for decades. We were instructed to fish only a floating line and dry flies (de-barbed, a strict regulation), tied onto 6X nylon and plenty of tippet, and to expect easily spooked wild trout.

Interestingly, this side of the Pyrenees, he told us, the brown trout are predominantly of the Mediterranean ‘zebra’ subspecies – subtly striped with faint black bars – whereas on the French side, where rivers run instead towards the Atlantic, they are regular browns. Unfortunately, Yvon said, unseasonably heavy rainfall had recently swelled the river, though there were signs of caddis, stoneflies and Mayfly about and decent fish (2 lb) had been caught recently. We headed over the bridge to the southern bank and made our way towards Hemingway’s dam – with which Yvon was familiar – along a narrow footpath, bordering colourful meadows of salvia, sainfoin, daisies and yellow rattle. The river, increasingly noisy beside us, revealed itself at intervals in a wonderful blue-green.

We got our first feel for the Irati just upstream of the dam, wading out into a strong current and casting upstream. I was pleased to recognise from my surroundings many elements described in the novel: the hills above and enclosing woods and ferns; the boiling water below and ‘the cold, smoothly heavy water above the dam’ that went ‘thundering down’. The springtime setting was just magnificent, all the wildness of a North American stream yet comfortingly European in scale. A light breeze, 14 degrees, but warming a little more with the sun. I fished for some time with a range of dry flies brought from home, while Dad, with Yvon, worked the river a little way downstream. I made for a trout rising 20 or so metres away, from a deep gully running along the opposite bank: I managed to entice a couple of rises but I was too slow with my strike.

Three important tips

The author on the Irati River

Yvon arrived behind me and began dispensing advice. While many useful tips were offered throughout the day, three simple principles informed the rest of the trip’s fishing, and led quickly to success: watch for a fish before any casting whatsoever, avoid drag, and set the hook quickly. And while these pointers may sound somewhat elementary, on a river like the Irati – with its fiercely timid trout – the former rule cannot be emphasised enough, however tempting it is to resist.

I hooked my trout moments after; a small but pretty brown of five inches or so, flanked with dark stripes; my first zebra. I left the water and with Dad and Yvon traced the bank in search of rising fish. This, I will say now, became true patience fishing. Yvon had us stalking the river for a good half hour before, having spotted a swirl, we were permitted to re-enter the current and cast. However, it was a chance to become well acquainted with the Irati’s local inhabitants; long green lizards in the knee-high grass, butterflies circling through the low hazel and beech; delicate orchids on the bank. Yvon enjoys a good deal of nature with his fly fishing, as of course did Ernest. “This is country”, exclaims ‘Bill’ in the book, as the pair walked ‘between the thick trunks of the old beeches and the sunlight came through the leaves in light patches on the grass’. At the next indication of a fish we climbed down onto a stony bank and Yvon lifted stones close to the water to reveal the many nymphs moving under them, and those yet to pupate. He was hopeful of a decent evening hatch.

Yvon handed out home-tied flies – lightweight sedges in yellow and black. “Tried and tested”, he said with confidence, “my flies stay very dry without use of false cast, which is important on the Irati”. We dressed them with Tiemco Dry Shake powder, greasing the leader and tippet also, and Dad continued along upstream while I went in for the rising trout. Knowing every inch of water here, Yvon was able to guide me along a narrow shelf of rock below the surface that put me out halfway into the river. Moments later, I had my second fish, a little larger than the first and fighting hard, though with too much excitement I lost it at the point of netting. Yvon laughed at my emotional swing from elation to thoroughly aggrieved; he’s in the business of teaching eager Englishmen patience with wild continental fish, and there would be plenty more in the river.

Dad casting on the Irati river

Around 7pm, Yvon left for the return drive over the Pyrenees, having shared a lunch of French bread, salami and cheeses on the riverbank and taken us back up beyond Aribe’s old stone bridge for the evening rise. (There, ever the naturalist, he’d pointed out wagtails criss-crossing the river feeding on insects; “a good indicator of a hatch”). The fish had gone quiet for much of the afternoon, though regulations permitted us to fish until 10:30pm, so we said goodbye to our spirited guide and waded hopefully upriver. The still-cool temperature (not exceeding 18 degrees, even by the late afternoon) meant that the grand hatch of Mayfly we were hoping for did not occur in earnest. Nonetheless, fish were rising at intervals along the bank, and casting for them against a beautiful orange sunset kept us contented, as did the extraordinarily good Navarra red wine when we retired to Hotel Aribe. Proprietor Marisa Rota made for a wonderful host, ever-obliging of my poor Spanish pleasantries and helpful with area maps and directions. The hotel was simple but enormously comfortable, and within earshot of the rushing river.

The next few days

The following two days unfolded much as the first; moments of suspense working over rising fish and a couple of small trout. I realised then that we were ambitious coming out only for a few days, and regretted such a short stay. I would recommend a longer week, perhaps at the tail end of June (fishing is only permitted in May and June), when heavy rainfall is more reliably behind. Nonetheless, as Hemingway put it, Navarra truly is country: I doubt I’ll fish as pretty a setting until I am next on the banks of the Irati, and I very much intend to return. Having seen enough fish – and some of them of a good size – I am confident that Hemingway’s beloved river may still live up to the image conjured on paper; under the shade of beech trees beneath cool Spanish mountains, far from frantic city life, pulling tough Mediterranean trout from a glinting green river.

The following week, back at home in the grey, I received an email from Yvon with photographs taken on his final Irati excursion of the season. Of course the trout pictured were big and beautiful, and the river much lower. I did my best to congratulate him with sincerity.

Discover more destination articles, HERE, or subscribe to our monthly magazine to receive 12 issues directly to your door.